Impacts on Insects

Life depends on water. Freshwater environments such as rivers and streams support fish, offer recreation opportunities and increase our overall quality of life. However, for more than a century, the health of America’s rivers and streams steadily declined. For these and other reasons, the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972. It requires states and tribes to evaluate the biological health of aquatic resources.

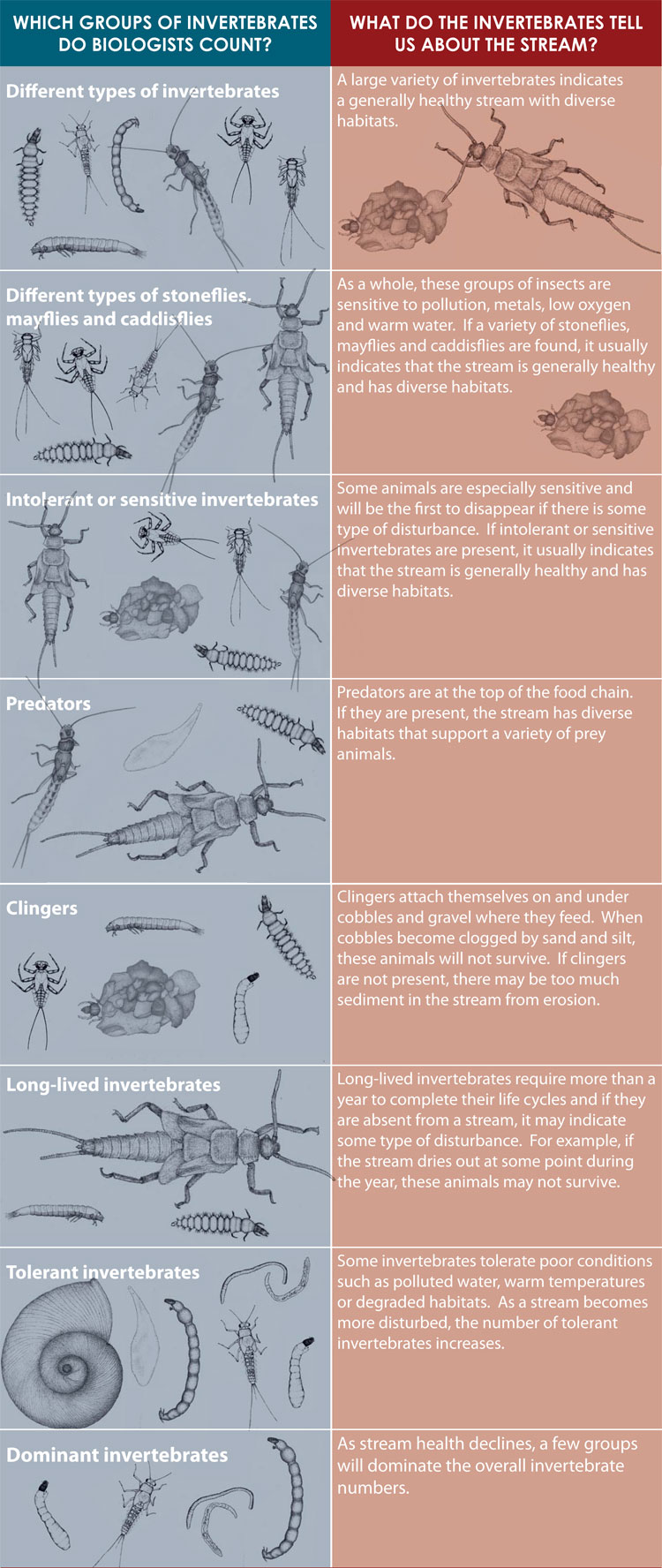

As we learned in Module 8: Insects, an effective way to determine the health of a habitat is to find out what lives there. This type of investigation is called biological monitoring or biological assessment. For streams and rivers, biologists look at invertebrates. They are especially good animals to use for stream assessments because invertebrate communities change in predictable ways when water quality or habitat changes. Some invertebrate groups are sensitive to pollution and habitat degradation. If these groups are found, we know that the stream is most likely healthy. Examples are mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies. Figure 1 gives a summary of useful ways to look at invertebrate communities, and what we can learn from them.

Figure 9.14: Aquatic invertebrate groups and what they can tell us about habitat and water quality.

Image from: How Healthy are Our Streams? City of Bellevue Biological Assessment (1998 – 2007)

Water quality and habitat changes can result from natural events, but most often pollution and disturbances in our landscapes are the result of human-caused impacts. For example, urbanization takes a large toll on the health of America’s aquatic resources. What are some of the reasons for this?

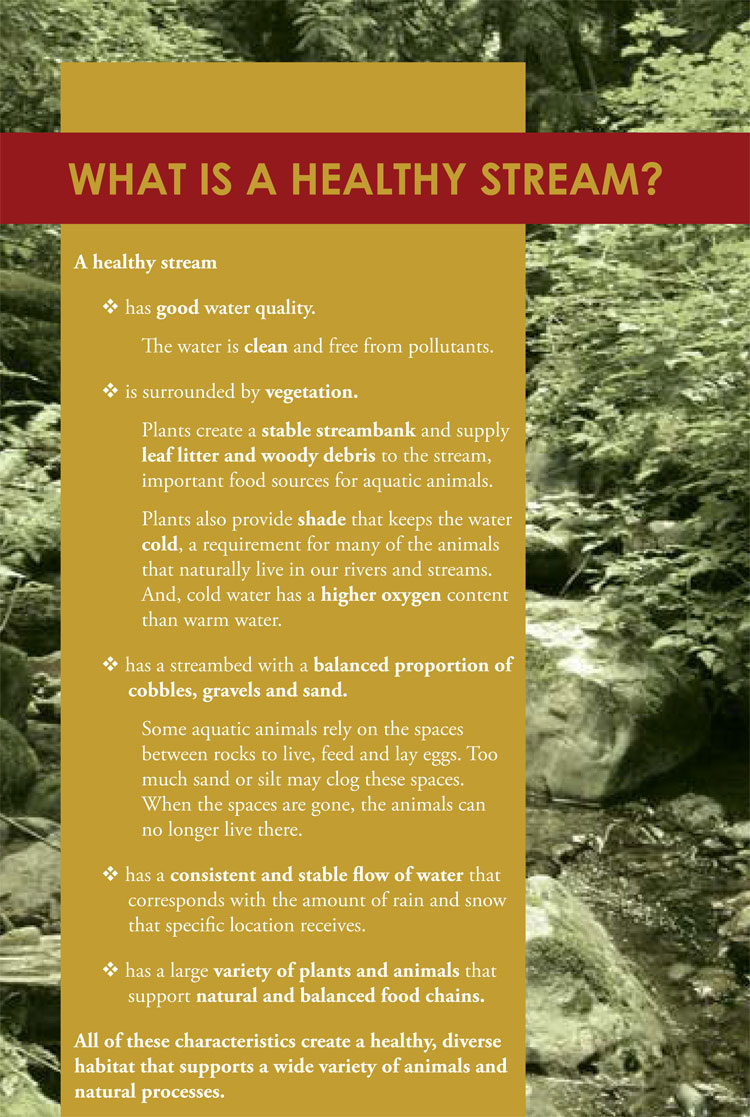

Cities are made of hard surfaces: roads, roofs and parking lots replace much of the natural landscape with hard, impervious surfaces. This can alter many of the characteristics essential to a healthy stream. See Figure 2 for a summary of the essential characteristics of a healthy montane stream. In fact, research has shown that even 10% impervious surface in a landscape can have an impact on stream health.

Figure 9.15: The essential characteristics of a healthy stream.

Image from: How Healthy are Our Streams? City of Bellevue Biological Assessment (1998 – 2007)

In a natural landscape, rainfall soaks into the ground and slowly moves toward the stream through the soil. This provides the stream with a gradual increase in water during rainy weather and makes it less likely that the stream will totally dry up in the summer season. When soil is replaced with asphalt and concrete, rainfall can no longer soak into the ground. Instead, rainfall pours off rooftops into gutters and downspouts and runs off roads, parking lots and sidewalks. This results in torrential flows that rush into streams, moving too much water downstream all at once. It also eliminates the precious reserve of water necessary to maintain stream flows during dry times.

The fast-moving water may erode the streambank, causing it to become unstable. The soil from the streambank is moved downstream, where it eventually settles and clogs the spaces between cobbles and gravels, removing habitat for some aquatic animals. The unstable streambank may not support shading riparian vegetation, eventually causing the water to become warmer, decreasing oxygen levels.

As rainfall pours over hard surfaces, it rinses away anything on the surface such as motor oils, fuels, detergents, de-icing compounds, pesticides, toxic metals and fertilizers. These substances end up in the stream, polluting the water.

Urbanization and its impervious surfaces are only one threat to streams. In a rural setting, indiscriminate logging of uplands can cause torrential flows to reach streams. Disturbance to the natural flow regime may also be caused by the straightening of stream channels, a common part of highway construction. Cattle grazing can lead to the degradation of riparian vegetation, with a resulting loss of streambank stability and shading and increased sediment in the stream. Inappropriate use of fertilizers on agricultural fields can result in the addition of nutrients to the water, which can promote the growth of nuisance algae and upset the balances of natural food webs.

Figure 9.16: Effects of stream condition (water quality and habitat integrity) on invertebrate communities.

Image from: How Healthy are Our Streams? City of Bellevue Biological Assessment (1998 – 2007)

As Figure 3 describes, aquatic invertebrate communities can indicate whether human impacts are affecting the health of a stream, and this type of analysis can also demonstrate differing degrees of impairment. The continuum from excellent to poor conditions is accompanied by the loss of some kinds of invertebrates, and, sometimes, replacement by other kinds. Additionally, changes to the energy balance, food webs, and function of streams are linked to these changes in invertebrate species.

Although streams are often thought of as simple conduits for the transport of water from mountains to the sea or to aquifers, their functions are actually more inclusive and complex. The energy balance of streams involves an elaborate spiraling of food substances used by invertebrates, beginning high in the headwaters and linked from reach to reach all the way to the mouths of rivers at the oceans. These food substances are made up of organic material such as leaves and twigs, which enter the stream as large particles. The large particles are processed and shredded by upstream invertebrates, and the smaller particles and fecal material that results are carried downstream and support invertebrates in lower stream reaches.

Impaired streams often have lost one or more links in this spiraling web of energy. Food webs are complex linkages between many organisms, from bacteria and fungi to plants and animals. Bacteria and fungi help to “condition” large organic material. Invertebrates feed on this organic material, as well as on algae, bacteria, and fungi. Fish feed on the invertebrates, and humans, eagles, bears and other terrestrial creatures feed on the fish. Disruption of aquatic food webs can result from alterations of the naturally occurring aquatic invertebrate communities, and these disruptions can thus be seen to have far-reaching consequences.

With the information you learned in Module 8, consider the following scenarios and discuss the results of human impacts on aquatic macroinvertebrates – and on humans as well.

- In Montana, water withdrawal for irrigation may result in severe losses of surface flow in rivers and streams, particularly in years of drought. Which invertebrate groups would be affected by reduced surface flows and why? How could you tell in June whether a stream had been de-watered the previous September?

- Using Figure 3, describe in words the species loss and replacement along the continuum from excellent stream condition to poor condition.

Visit the Forum: Impacts on Insects to discuss these questions, or leave a comment below to get feedback from the MSP team.