Migration

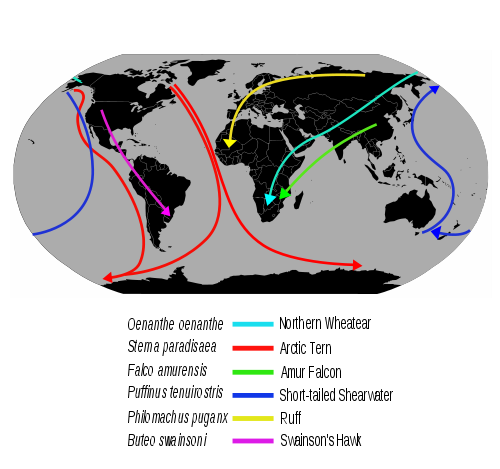

Figure 6.63: Examples of bird migration routes.

Image from URL: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Migrationroutes.svg

In any given area some birds have the survival mechanisms necessary to survive the harshest of winters or scarcity of food. These “resident” birds do not follow seasonal cues to leave one area for another. Many bird species, however, embark on an annual seasonal journey called migration. The hallmark of migration is its regularity in response to the changes in seasons. Some birds may leave an area because of changes in food availability or habitat or invade new territory. These irregular bird movements are not considered migrations but instead are called nomadism, invasions, dispersal or irruption.

Birds can be classified as one of the following:

- Permanent residents, or just “residents,” are non-migrating birds such as House Sparrows who remain in their home area all year round.

- Summer residents are migratory birds such as Purple Martins who arrive in our northern backyards in the spring, nest during the summer, and return south to wintering grounds in the fall.

- Winter residents are migratory birds who have “come south” for the winter to our backyards. White-throated Sparrows, who are summer residents in much of Canada, are winter residents in much of the U.S.

- Transients are migratory species who nest farther north than our neighborhoods, but who winter farther south; thus we see them only during migration, when they are “just passing through.”

Migratory patterns often follow virtual bird highways – called flyways. Many bird species fly north in the spring and breed in the temperate Arctic summer and return in the fall to warmer wintering grounds in the south. Migration is often accompanied by massing. Huge flocks of birds – sometimes of a single species and sometimes of mixed species – gather in the spring and migrate en mass to their breeding grounds. Huge flocks of snow geese, tundra swans and Ross’ geese are a welcome spring visitor to Montana as they continue on their northward journey towards their traditional breeding grounds.

Figure 6.64: Freezeout Lake near Augusta Montana is a favorite gathering spot for these birds as they gorge on barley in stubble fields early in the morning then fly to the lakes.

Image by Lorna McIntyre.

Videos of migrating snow geese at Freezeout Lake:

- Snow Geese Migration at Freezeout Lake (Mefeedia)

- Freezeout Lake 2009 (Vimeo)

These long journeys can be incredibly stressful. Some birds do not feed during their migratory journeys and must rely on stores of fat to see them through to journey’s end (for more, refer to Birds Fuel Up on Super Foods Before Migrating from Discovery News). Predators like the Greater Noctule Bat are attracted to the masses of flying birds and will often snatch hapless passerines on their way. Studies have shown that these very large bats with a 46 centimeter wingspan (fortunately found in Europe, Africa and Asia) feed almost exclusively on migrating birds passing through in Spring and late summer. Studies of their guano during these periods has shown that about 70% of its mass is bird remains. For more details, refer to the article Bat predation on nocturnally migrating birds from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and Bats’ Conquest of a Formidable Foraging Niche: The Myriads of Nocturnally Migrating Songbirds from PLoS ONE.

Figure 6.66: Predators like the Greater Noctule Bat are attracted to the large numbers of migrating birds and will often snatch hapless passerines on their way.

Image from URL: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:GreaterNoctule.JPG

Despite the incredible amounts of energy expended by birds in their epic migrations, the primary advantage of migration is conservation of energy. Birds are generally flying farther north (or farther south, south of the equator) to take advantage of the explosion of vegetation that accompanies long summer days farther from the equator. The extended daylight hours allow diurnal birds (active by day, sleeping at night) to produce larger clutches than those of related non-migratory species that remain in the tropics year round. As the days shorten in autumn, the birds return to warmer regions where the available food supply varies little with the season.

Much of the mechanics of migration are under genetic control. These include timing and response to important physical stimuli like duration of light. The primary physiological cue for migration appears to be the changes in the day length. These changes are also related to hormonal changes in the birds. In the days before migration, even caged birds display a restlessness in their behavior. This heightened activity or “Zugunruhe” is accompanied by other physiological changes including increased eating behaviors and fat deposition.