Nests & Eggs

|

Bird |

Incubation Period |

|

Chicken |

20-22 days |

|

Ostrich |

42-50 days |

|

Parakeet (budgie) |

27-28 days |

|

Pigeon |

14-18 days |

|

Swan |

30 days |

|

Toucan |

18 days |

Birds bear their young in hard-shelled eggs which hatch after some time. Some birds, like chickens, lay eggs each day, while others (like the maleo) may go for years between laying eggs. Birds build nests for breeding in trees, on cliffs, or on the ground. Most birds are taken care of by at least one parent until they are able to fly and get their own food. The incubation period of bird eggs varies from species to species. There’s also some variability due to the temperature.

The most visible thing about an egg is the shell itself. Non-passerines tend to lay all white or cream-colored eggs – unless they are ground nesters – while passerines often lay colored or textured eggs. The white eggs of cavity nesters like Northern Flickers, Owls and Downy Woodpeckers (all non-passerines) are hidden in dark holes from predators looking for the ultimate taste treat of fresh eggs. Ground nesting birds rely on cryptic coloration to help their eggs “hide in plain sight.”

Figure 6.54: Bird eggs come in a very wide variety of sizes and colors.

Image from URL: http://people.eku.edu/ritchisong/554images/bird_eggs2.jpg

Color is added to the shell in the uterine region of the genital tract. The various colors are derived from pigments obtained as breakdown products of blood. Red, brown and black pigments come from hemoglobin, while blue and green pigments are bile derived. The colors are added in patches as the egg moves through the tube. The pattern of the colors, i.e. whether it has dots, streaks or swirls, is controlled by the speed of the egg as it passes through the uterus and the degree of turning it undergoes while passing through.

Figure 6.55: Birds’ eggs, like the birds themselves, vary enormously in size. The largest egg from a living bird belongs to the ostrich. It is over 2000 times larger than the smallest egg produced by a hummingbird.

Image from URL: www.royalalbertamuseum.ca

/vexhibit/eggs/vexhome/sizeshap.htm

Eggs differ greatly in the thickness of the shell. Many wading birds have thin-shelled eggs while birds like Ostriches have extremely thick shells. Imagine the weight of an adult Ostrich on the nest and you can appreciate the need for the extra strength packaging. The eggshell is made of calcium carbonate, CaC03, which is collected by the female all year and stored in her leg bones until needed. In this way she can collect enough calcium carbonate from her food to make all the eggshells she needs during the brief egg-laying period.

Check Your Thinking: Can hens lay eggs even if there is no rooster around for copulation?

Ostrich eggs are about 180 mm long and 140 mm wide and weigh 1.2 kg. Hummingbird eggs are 13 mm long and 8 mm wide and they weigh only half of a gram. The extinct Elephant Bird from Madagascar produced an egg 7 times larger than that of the Ostrich!

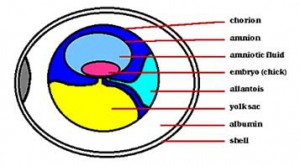

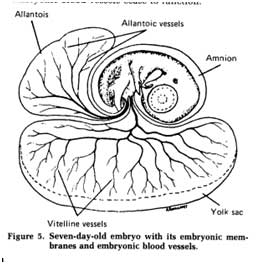

Within the egg, there are three extraembryonic membranes that support the life and growth of the embryo:

- amnion

- surrounds only the embryo

- inner layer of cells secretes amniotic fluid in which the embryo floats; fluid keeps the embryo from drying out and protects it

- chorion – surrounds all embryonic structures & serves as a protective membrane

- allantois (or allantoic sac)

- grows larger as embryo grows, fuses with the chorion & is called the chorio-allantoic membrane

- works together with chorion to permit respiration (exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide) and excretion

- important in storage of nitrogenous wastes (uric acid)

The following sites contain more comprehensive info on avian reproduction:

- Avian Reproduction: Anatomy & the Bird Egg from Eastern Kentucky University: This is an outstanding, comprehensive website for a deeper dive into reproduction in birds.

- Nests and eggs that may show up in bluebird nestboxes from Sialis: This is a great site for looking at eggs and nest box inhabitants. It is an east coast website, but many of the birds can be found here as well.

- North American Bird Egg Set from Bone Clones: This page shows a set of eggs from a variety of North American birds, along with a key. To view a larger version of the egg set, click here.

Figure 6.58: Mockingbird eggs and nest.

Image from URL: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mocking_Bird_eggs.JPG

Figure 6.59: Robin eggs and nest.

Image from URL: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Animaldetectorrobineggs.jpg

Figure 6.60: Killdeer eggs and nest.

Image from URL: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Killdeer_eggs.jpg

Figure 6.61: Hummingbird eggs and nest.

Image from URL: http://howtoenjoyhummingbirds.com/hummingbird_nests.htm

Wild Bird Eggs for Sale is a Norwegian website that identifies many specimens of eggs collected between 1870 and 1979. Unfortunately, the common names are all in Norwegian. However, and the Latin taxonomic names transcend language barriers.

Figure 6.62: This Reed Warbler is raising the young of a Common Cuckoo, the best-known cuckoo.

Image from URL: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Reed_warbler_cuckoo.jpg

Birds build nests for breeding in trees, on cliffs, or on the ground. Some birds build their own nests, some birds only use the abandoned or active nests of other birds. Some birds lay their own eggs on top of the eggs of another bird. The host will often care for the “parasitic” young at the expense of their own offspring. This type of nest parasitism or brood parasitism can be either intraspecific (within the same species) or interspecific (with different species).

Cowbirds are parasitic birds—they lay their eggs in the nests of other birds (host birds) and let the other species feed and care for hatchlings. The Brown-headed Cowbird, very common in North America, and the Shiny Cowbird will lay eggs in the nests of hundreds of different species. Some Brown-headed Cowbirds apparently specialize in parasitizing particular host species. Cowbirds scan for nests in which to lay their eggs. They tend to search near their foraging areas in agricultural areas where there are abundant seeds, urban areas, and grasslands bordering forests. Thus, host species’ nests in these areas are parasitized more often than nests in other habitats. The female cowbird watches and waits until the host bird begins laying. Then she pays a quick visit to the host nest, lays an egg and leaves. Four or five eggs may be laid in the same host nest, mixed in with the host’s clutch. In some cases, cowbirds remove host eggs from the nest to make room for their own.

For more information on nest parasitism, visit Brood Parasitism from Stanford University or Conspecific nest parasitism is associated with inequality in nest predation risk in the common goldeneye from the Journal of Behavioral Ecology.

Here are some great videos of nesting and nest-building birds (all are from YouTube):

- Bald Eagle Nest Building

- It’s Hard Work Building a Nest (Bald Eagles)

- Hummingbird Nest Documentary (Hummingbirds hatching, developing and flying away over a 40 day period)

- Mother Hummingbird Building Nest

For an excellent reference book on nesting, refer to Eggs & Nest by Rosamond Purcell, Linnea S. Hall, and René Corado.