Bird Locomotion

Although most birds can fly, not all flying animals are birds. For example, many insects also fly. Birds have a very strong heart and an efficient way of breathing – these are necessary for birds to fly. Birds also use a lot of energy while flying and need to eat a lot of food to power their flight. As we have learned, flying birds have strong, hollow bones and powerful flight muscles.

Not all flying animals are birds, and not all birds can fly. The ability to fly has developed independently many times throughout the history of the Earth. Bats (flying mammals), pterosaurs (flying reptiles from the time of the dinosaurs that were NOT dinosaurs), and flying insects have flight mechanisms that are quite distinct from those of birds.

Figure 6.41: The osprey pictured above is well-adapted to plunge into water mid-flight to catch fish.

Image from URL: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Osprey_(Pandion_haliaetus)_near_Kawal_WS,_AP_W.jpg

Bird locomotion is quite varied; most can fly, some can run very well, some swim, and some do combinations of these. Flying birds’ wings are shaped to provide lift, allowing them to fly. These light-weight animals have adapted to their environment by flying, which makes them efficient hunters, lets them escape from hungry predators (like cats), and takes them away from harsh weather (migration).

For more, refer to the following videos from National Geographic related to bird locomotion (note: all videos will start with a commercial):

The Origin of Flight

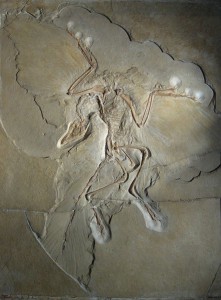

Figure 6.42: An Archaeopteryx fossil specimen displayed at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin.

Image from URL:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Archaeopteryx

Some scientists support the arboreal, or “from the trees down”, hypothesis (e.g. Feduccia 1996) and suggest that the ancestors of Archaeopteryx lived in trees and glided into flapping flight.

Others argue that the claws of Archaeopteryx weren’t suited to climbing, supporting the cursorial, or “from the ground up”, hypothesis (Burgers and Chiappe 1999). Scientists have suggested that these ancestors used their long, powerful legs to run fast with their arms outstretched, and were at some point lifted up by air currents and carried into flapping flight (Gould 1999).

Studying living animals can throw light on their evolutionary past. Ken Dial (2003) of the Flight Lab at the University of Montana noticed the ability of gamebird chicks to escape danger by scrambling up vertical surfaces. The chicks first run very fast, flapping their immature, partially feathered wings, frantically creating enough momentum to run up a vertical surface to safety. Could this mad scramble for survival be the origin of flight?

And finally, James Carey, a UC Davis demographer and ecologist, has proposed that the evolution of flight in birds is linked to parental care (Carey and Adams 2001).

Whatever the origins and however they came into play, dinosaurs, and birds, eventually took to the air.

Exactly how birds acquired the ability to fly has baffled scientists for years. Archaeopteryx provided a starting point for speculation. Built like a dinosaur, but with wings, scientists guessed at how a hypothetical ancestor might have taken flight.